Saskia’s story.

Stroke at 22.

At 22 I was hyper-independent, throwing myself into running my new business, enjoying the gym and travelling city to city at the weekend. Life was busy and I was in control. Then, in an instant, everything shifted. I had to trade my self reliance for complete dependence on others, for everything.

It started after I’d been on a few rides at Southend Pier. Not long after I got off, I felt an intense, overwhelming pressure spread across my whole head. It was heavy and strange. I travelled alone on the train all the way home with the pressure still lingering and went to bed. I woke the next morning to find it slightly less intense but still unsettling. I tried to ignore it, so I decided to have a nap. The sort of thing you do when you have a headache.

Later, my sister woke me as we were heading to our gran’s. Just as we were leaving, a sharp, striking pain shot through my head. I think my family thought I was being dramatic as I was known to overreact at the smallest of things. But I took paracetamol, which was unusual for me as I’d always avoided painkillers, saying they didn’t work. On the 30–40 minute drive, I sat silently in the back seat. My family thought I was asleep. I wasn’t. I was wide awake, trapped in excruciating pain, unable to open my eyes or tell anyone how bad my headache really was. I now know this is described as a thunder clap headache.

As I stepped out of the car and walked down her driveway, I genuinely felt like I wasn’t alive. We got inside and my gran was asking me if I wanted a drink, I could barely answer her and felt rude, but just put it down to how much pain I was in. Minutes later, I threw up. My dad was trying to talk to me but I couldn’t reply. “Saskia can you hear me?” I was shouting internally but the words just weren’t there. I was suddenly completely mute and very confused. With no ambulance available, my dad carried me to the car and I was violently sick the entire journey.

We arrived at Gloucester Royal at around 3pm. Everything was a blur until I had my CT scans, the final one being with contrast dye. Lying there I genuinely believed nothing was wrong with me, despite the pain and the fact my speech had been taken away. Looking back, I think my body was protecting me and keeping me calm.

After the scans, everything happened fast. I was rushed to the Resus room where they explained I had a bleed on the brain. A haemorrhagic stroke. At 22. My family were in disbelief, trying to process what they were being told about what would happen next.

They explained an ambulance was on the way to transfer me to Southmead, Bristol where a team of specialists were waiting. I was wide awake through all of this. Then at 3am, I was taken in the ambulance where my parents had to drive to meet me.

I was placed in the ICU, surrounded by wires and machines, with several cannulas in my arms. It was there that the neurology team explained I had suffered an AVM rupture after a build up of pressure. An AVM (arteriovenous malformation) is a tangle of abnormal blood vessels connecting arteries and veins in the brain. It’s a congenital defect, meaning I was born with it, and most people never even know they have one until it ruptures. In my case, the rupture changed everything. When my dad asked if it had stopped bleeding, they informed him that if it had not, I would be dead. I’d never even heard of an AVM. I didn’t know I was living with this ticking time bomb inside my head.

Not long after, I was told that the problems with my speech were caused by Aphasia and Apraxia. Aphasia is when the brain’s ability to process language is damaged, so it affects finding words, understanding, reading, and writing. Apraxia is when the brain struggles to send the correct signals to the muscles needed for speaking, even when you know exactly what you want to say. Together it meant I couldn’t say a word. The speech and language therapists were also worried that I might not be able to swallow safely. For the first four or five days, I lived off of baby food pouches. Even something as basic as eating suddenly felt impossible, like another part of my independence had been taken away. I could just about hum ‘twinkle twinkle’ with my speech therapist.

After a few days,when I finally had the strength to hold my phone without dropping it, we realised I could still type. That became my only lifeline to communicate, and I’ve kept all of those notes. Reading them back now, they’re actually hilarious. A collection of broken, one-sided conversations where I was trying so hard to make myself understood. Every single word felt like a battle. I would sit there, straining to find the right one, only for me to type the wrong instead. It was exhausting and frustrating, but I was happy to have found a way to communicate.

After about a week in hospital, some of the fluid from my brain became trapped on my spinal cord. That was the worst pain of all. Every two hours I was given different painkillers, but nothing touched it. All I could do was cry from the pain, unable to properly communicate what I was feeling.

As soon as I was moved out of the ICU and onto the neurology ward, I felt like I had gained back a tiny bit of independence. For me, that meant one thing above all else, a shower. No matter how much pain I was in, I was determined to get up and shower every single day. It wasn’t easy. I had to sit on a shower chair and rely on help, like my step mum washing my hair, but it made me feel human again. I even managed to shave my legs - a small thing, but it felt like “typical me” was coming back. Getting dressed afterwards was another story. The pain made it difficult,so my mum had to help me put on clothes and the simplest tasks became exhausting. On top of that, I still had no speech. My stepmum came up with an idea that changed everything for me: picture flashcards. Each one had something I might need: pain relief, towel, blanket, lip balm, toilet — so I could show exactly what I needed instead of struggling to type.

A group of neurosurgeons came to discuss my options. The choices were terrifying: radiation or a craniotomy (brain surgery). Radiation could take years and might not fully resolve the problem, while the craniotomy was invasive, risky, and life-changing but it was the only option that offered hope of a full recovery. I chose the craniotomy. I had an angiogram for them to be able to locate exactly where to make the incision. This is an X-ray procedure that uses a thin tube (catheter) which is inserted into the femoral artery in the groin to examine blood vessels. Then, on Friday 2nd May, I was taken down for surgery, which lasted 7.5 hours and was a success. Mario Teo, my surgeon, had described it as “easy brain surgery”.

I stayed in hospital over the weekend for further CT scans and was discharged on the Tuesday, as home was the best place for me to begin recovering. Just one day after being discharged I was readmitted to Gloucester Royal after experiencing severe dizziness and sickness. After more CT and MRI scans, they confirmed I had vertigo and nystagmus as transient side effects of the surgery. In a way I think that was the universe preparing me for a recovery that wasn’t going to be linear. I had genuinely believed that I’d be back to working and going to the gym within two weeks. I had no idea what was to come.

It’s now been six months since my stroke, and though everyone says that’s still very early in recovery, my world has completely changed. One day I was living life as normal, and the next I was in a hospital bed. Now I wake up facing challenges I’d never imagined: debilitating fatigue, constant pain, insomnia, nightmares and sensory struggles so intense that even listening to music can drain me.

Mobility has been one of the hardest parts. When I walk I'm very slow and unsteady on my feet. Mostly down to fatigue. I rely on a wheelchair, and while I’m grateful it gives me freedom to move, it also reminds me every day of what I’ve lost. At times I even feel like a fraud sitting in it. People see me in the chair and, because I’m young and sometimes able to take a few steps, I worry they assume I don’t need it - or worse, that I’m exaggerating. Just because I “look fine”. Which is bizarre because before I never cared what anyone thought of me. What they don’t see is how quickly fatigue causes me to crash, how walking even a short distance can completely wipe me out, leaving me in pain and forcing me to spend hours, sometimes days, recovering in bed. Struggling to listen to music or watch tv because having neuro fatigue means processing information drains you. Fighting fatigue only slows my recovery, so I’ve learned to listen to my body and rest when I need to.

One of the biggest milestones was regaining my speech. Words returned slowly like a toddler learning to talk. I absorbed every word I heard, only to forget it after I’d said it. When I finally had all my words back, I found starting conversations surprisingly difficult. It wasn’t until later that I realised why: I simply had nothing to talk about, because I wasn’t really doing anything. I wanted to talk about my stroke, but I worried I’d be a burden. Yet being able to communicate again was huge for me as I had always been such a chatterbox, and losing that part of myself had felt like losing a piece of who I was. Even now, if I'm anxious I struggle to get my words out.

I grieve my old self. I miss how effortlessly I used to live, the energy I didn’t even realise I had, and the sense of normality that still feels out of reach. As much as I miss my old self, I’m also glad I’ll never have her mindset again. I know a lot of survivors will relate to this. This whole experience has made me see the world differently, notice the little things, and really value resilience, patience, empathy and gratitude in a way I never did before.

Through it all, my family never left my side. My parents were there every single day during visiting hours, 11am to 7pm without fail. My brother came daily after that first time he’d seen me, and my sister came whenever she could, even while studying for her A levels. My two best friends visited me in ICU on the very first day and then continued to visit, and other family members came every few days, giving me breaks from the ward, in the wheelchair, to go and sit in the hospital gardens or Costa. My mum, sister and auntie got me new pyjamas and things I'd need to feel fresh while in hospital. That unwavering support from my small circle has carried me through and given me a sense of normality when nothing about my life was ‘normal’.

I've never tried to hide from stroke. If anything, I’ve become obsessed with learning about it. My dad found ‘Different Strokes,’ and discovering other young survivors’ stories changed everything. Reading them made me feel understood, and even led me to meeting Kyra, who shared her own story and has since become a good friend who I can actually relate to.

With my wider circle, conversations often stay at surface level, while I’m living with a depth I never asked for. It isn’t their fault. Before this happened, I would’ve been the same, living in that kind of innocence. I love my friends, but I also know they’ll never fully understand this new version of me. Sometimes, I catch myself feeling frustrated or upset when they talk or post on social media about their plans that I know I can’t manage. I realise that I’m not frustrated with them, it's just that their lives are a mirror of the past to me, a version I can’t reach right now. In a strange way, I’m grateful that they’re untouched by this, because I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. But I can’t help envying how freely they live their lives, doing all the things I can’t right now, or probably for the next two years or so.

I know, though, that eventually my mobility will return, and I’ll be able to go back to the gym. I know the fatigue will ease, and I’ll be able to work, enjoy concerts and city breaks again. Though I’ll probably live with some of it forever. I feel fortunate for this though, because I know not everyone gets that chance, and I know my age plays a huge role in that. I also know that over the next few years, things will continue to improve, step by step, as I rebuild my strength and stamina. It’s a slow process, but knowing there’s a future where I can reclaim parts of my old life keeps me going.

I have an angiogram in November 2025, and another in three years, to make sure the AVM hasn’t returned and ensure it won’t happen again. In the meantime, my family are planning a 33 mile charity walk for Southmead on my surgery anniversary. From Gloucester Royal to Southmead. Both to thank the neurology ward who saved my life and to raise awareness of young stroke. I’m hoping I'll be able to get involved, even if I just walk the start and very end.

For people in my age group, 18 to 25, there’s almost no support - and for family members of stroke survivors, there’s absolutely nothing. That has to change. My family has gone above and beyond for me, and I feel guilty for putting them through all of this. My dad has listened to several survivor story podcasts learning everything he can about stroke to support me, and my family’s dedication has been overwhelming. My brother and sister have been there for me even when I don't need them to.

When people read my story, they’re shocked for a moment, maybe send their best wishes, and then move on. I don’t get that luxury. I live it every single day. Most people see the word “stroke” without understanding it. I know many of you reading this will relate. Before it happened, I wouldn’t have either. What hurts is how quickly it becomes a passing thought for others, while for me it’s constant. Every movement I struggle with, every wave of fatigue, every reminder that life has changed and it’s my reality. For them, it’s a story. For us, it’s life. Some days I can barely string a sentence together. That’s exactly why I’m taking action to raise awareness, to make stroke something people truly understand, and to make sure it’s more than just a word they skim past.

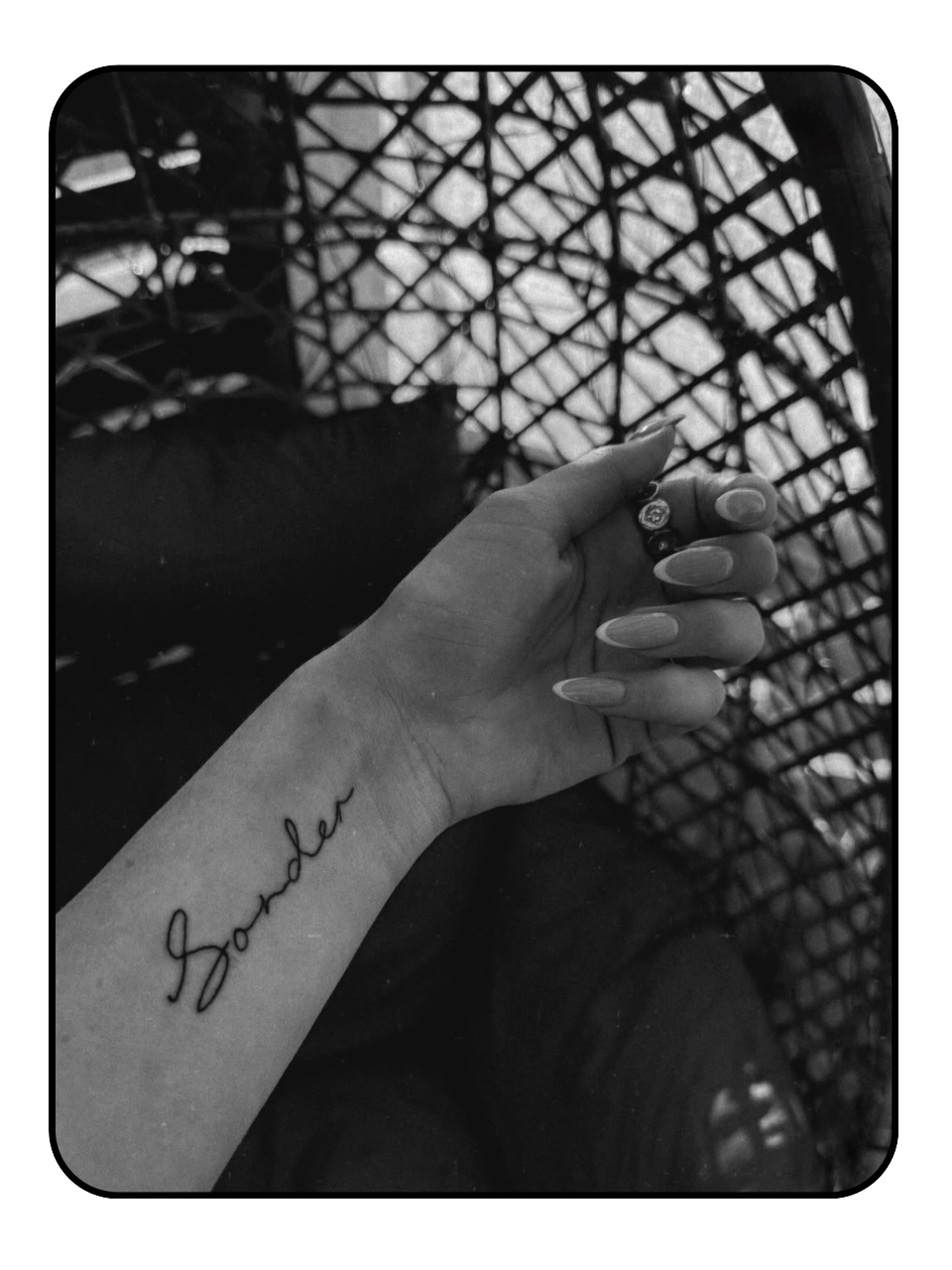

I had wanted a tattoo of the word ‘sonder’ since the beginning of the year. Sonder - the profound realization that every passerby you encounter is living a life as complex and vivid as your own. I’ve now had this done and my dad and step mum got it too. This experience has changed everything for me. But oddly, I’m thankful. It’s given me a new way of seeing the world. One where the smallest things feel worth celebrating, and where I know I’m still here, still moving forward. I don’t want this to define me, and I don’t want to suffer in silence while people feel sorry for me. I’m not feeling sorry for myself - instead, I’m taking something really bad that happened and turning it into a positive. Of course I have my moments, and you’re allowed to. I’m in a position now to help others, to raise as much awareness as possible, and to make real change. I want to be a voice for the survivors who now have disabilities, speech issues (aphasia), or cognitive challenges that make it harder for them to speak up or they feel uncomfortable to do so. Even if one person reads this who can relate in any way and feel seen then it’s worth it.

I could go on and on about this journey, but nothing could ever fully capture everything that has happened, and continues to happen.

This September, five months in, I travelled to Greece with my two best friends who were there from the very beginning, on the worst days. It wasn’t the same as my old holidays as I can’t do everything spontaneously or like I used to, but it’s a step forward. Recovery has taught me resilience, gratitude, and pride in how far I’ve come, and I’m still finding so much joy in this unpredictable, beautiful little life.